March 2009 update: New excavations by the Centre for Global Archaeology Research at Universiti Sains Malaysia have unearthed evidence for an iron-smelting facility in the Bujang Valley, dating to 300CE and the earliest example for Malaysia. See here and here.

When the British acquired the island of Penang from the Sultan of Kedah, they probably did not realise that they were just 40km away from ancient settlement that once also was a port of call for traders entering the Malacca Strait. The settlement in the Bujang Valley dates as far back as the 5th century, and as I was in Penang the couple weeks ago to see my supervisor, it was impossible to not make a side trip to one of Malaysia’s most underrated archaeological sites.

The many names of the Bujang Valley

The Bujang Valley rests at the foot of Gunung (Mount) Jerai, a major navigational landmark for ships coming from India. For sailors traveling from India without hugging the coast Gunung Jerai would have been a welcome sight after sailing for weeks without seeing any land. At various times in history the Indians knew the kingdom as Kalagam (according to a 2nd century Tamil poem), and later on Kadaram or Kataha. The Chinese Monk I-Tsing (I-Ching) who traveled to India in the 7th century to visit the University of Nalanda would have known Bujang Valley at Qie-zha (sometimes spelled Chieh-Cha or Kie-tcha). Arab traders knew of the same place as Kalah or Kalahbar.

Bujang Valley today, facing approximately North-east. Notice Gunung Jerai in the background.

Buddhist and Hindu influences

The Bujang Valley was surveyed in the 1930s by Quartritch Wales, who found some 30 sites in the area (some 50 sites have been found to date). In particular, the area known as Sungei Mas, which would have been a logical place for landfall, yielded a number of trade artefacts and Buddhist monuments. It seems that kingdom at Bujang Valley between the 5th and 11th centuries was Buddhist, and then later on became Hindu. This shift if religion can be explained by the Chola occupation in the 11th century. The Tamil kingdom mounted a swift attack through the Straits of Malacca, conquering the culturally-significant Kataha, as well as plundering the main ports of Srivijaya. Tamil occupation of Kataha was short, lasting about a century, but the cultural and architectural influences carried on until today. Some of the most significant temples – known as Candi (pronounced Chandi) – that populate the valley have a distinct South Indian influence.

Candi Bukit Batu Pahat

The centrepiece at the Bujang Valley archaeological museum is Candi Bukit Batu Pahat, which was built around the 11th and 12th century – contemporary to Angkor Wat. The candi was made from granite quarried nearby and overlooks the valley from its high point.

The candi retains the Vimana (closed room) and Mandapa (pavilion) template that is typical of Hindu temples. The Vimana would have housed the statue of the deity, and excavations have unearthed stone reliquaries containing semiprecious stones, gold and silver foil relics.

More significantly, Candi Bukit Batu Pahat is a rare example of Hindu temple architecture outside of India. Notice these drains? Worshipers would place their oblations of holy liquids, usually offerings of water and ghee to the deity in the vimana, and collect them as they poured out of the drain to the side. These drains are very rare in Southeast Asia, but common in South India. Typical Indonesian Hindu temples do not have this architectural feature, which suggests that Bujang Valley has a close connection to India, rather than an indigenised form of Hinduism.

How local is the granite from Candi Batu Pahat? A river runs through the grounds of the Bujang Valley Archaeological Museum, and on its banks you can still see the remains of quarried granite blocks that were never used.

Other reconstructed Candis

Because Bujang Valley encompasses a large area, most of the candis exhibited at the museum are reconstructions of the original finds, moved to the vicinity of Candi Bukit Batu Pahat which is the only candi that rests in-situ. This is rather unfortunate, because we have no way of ever knowing if these reconstructions are accurate. I find it interesting to note that some of these reconstructed candi are reminiscent of the structures from the Cat Tien archaeological site in Vietnam which was discovered in the last decade.

Candi Pendiat is an 11th century structure built of laterite with the Vimana-Mandapa structure. Interestingly enough, a small bronze Buddha was found within it despite the strong Hindu architecture.

Candi Pengkalan Bujang has a cruciform shape to it, and a smaller basin-like structure associated with it. It is built of brick.

Candi Bendang Dalam is another Hindu temple with the now-familiar Vimana-Mandapa format. It is also made of laterite, and here you can clearly see the post holes where the wooden hafts would have been inserted to make pillars.

Bujang Valley today

Like much of non-urban Malaysia, Bujang Valley today is plantation land – either oil palm , rubber or rice. In that sense, perhaps the decision to move the candis from their original sites was a good idea. The distribution of the 50 candis around the Bujang Valley as well as the tropical environment reminds me of how quickly Angkor was overtaken by nature. Perhaps with the right Geographic Information Systems tools, we might one day uncover the urban spawl of the Bujang Valley too?

Bujang Valley from far. Notice the curve of the Merbok river and the opening to the sea. This is where ships would have made landfall.

The grounds of the Bujang Valley Archaeological Museum. Candi Bukit Batu Pahat is the rectangular gray structure on top.Next week, I’ll talk more about the Bujang Valley Archaeological Museum. The Bujang Valley Archaeological Site is about an hour’s drive away from Penang, which is about four hours away from Kuala Lumpur. To get there, take the North-South Highway and exit via the Sungei Patani (North) turnoff. The GPS coordinates for the Bujang Valley Archaeological Museum is 5°44’15.51″N 100°24’49.68″E.

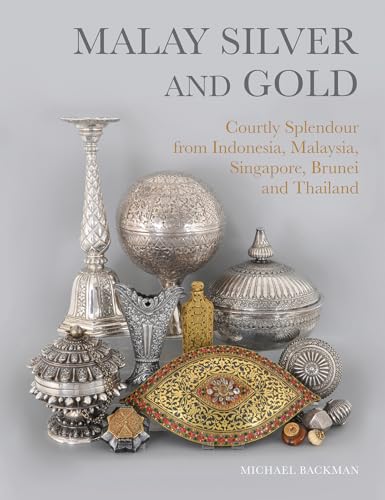

Related Books:

– Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula by P. M. Munoz

– Early History (The Encyclopedia of Malaysia) by Nik Hassan Shuhaimi Nik Abdul Rahman (Ed)

Thanks Noel for posting this. I am interested in ancient sea ports in South East Asia and this was one place I did not know about. Have you been to Nakhorn Si Thammarat in Thailand? I think you will like the museum there.

Hi Preetam! Thanks for the support. Yes, I have heard of Nakhon Si Thammarat – it used to be called Ligor – although I have yet to visit it. Hmm… maybe I’ll write something about the ancient ports of Southeast Asia one of these days. =)

thanks for featuring these sites. Very few know that there are ancient Hindu-Buddhist temple complexes in malaysia! If the Malaysian govt work a little bit harder to promote these sites, malaysia’s Bujang Valley temples would be on international tourists’ maps!

True, it’s a such a shame because the Bujang Valley complex is just an hour’s drive away from Penang – and Penang already draws a lot by way of tourists that it’s not too much of a stretch to organise side trips there. In any case, I’m glad you enjoyed the post. =D

hiii…thanks for the loveLy info on Lembah Bujang. Was wondering, what about the local people in Lembah Bujang back then, were there any or society emerge only after the Indians and Chinese traders came? 🙂

Hi ienone,

that’s pretty hard to say – i don’t think we can take for granted that just because the architectural styles were Indian means that the population was Indian. More likely, the population was local and adopted Indian, Hindu and Buddhist practices. We see that kind of pattern (adoption of Indian social structures) happening throughout Southeast Asia at the time, eg Champa, which was contemporary to the Lembah Bujang civilisation.

Sri Lanka has a large number of arhaeological heritage sites, so this conference is very important to Sri Lankans to exchage their ideas.

hi

thank you so much for sharing all the information

(history teacher)